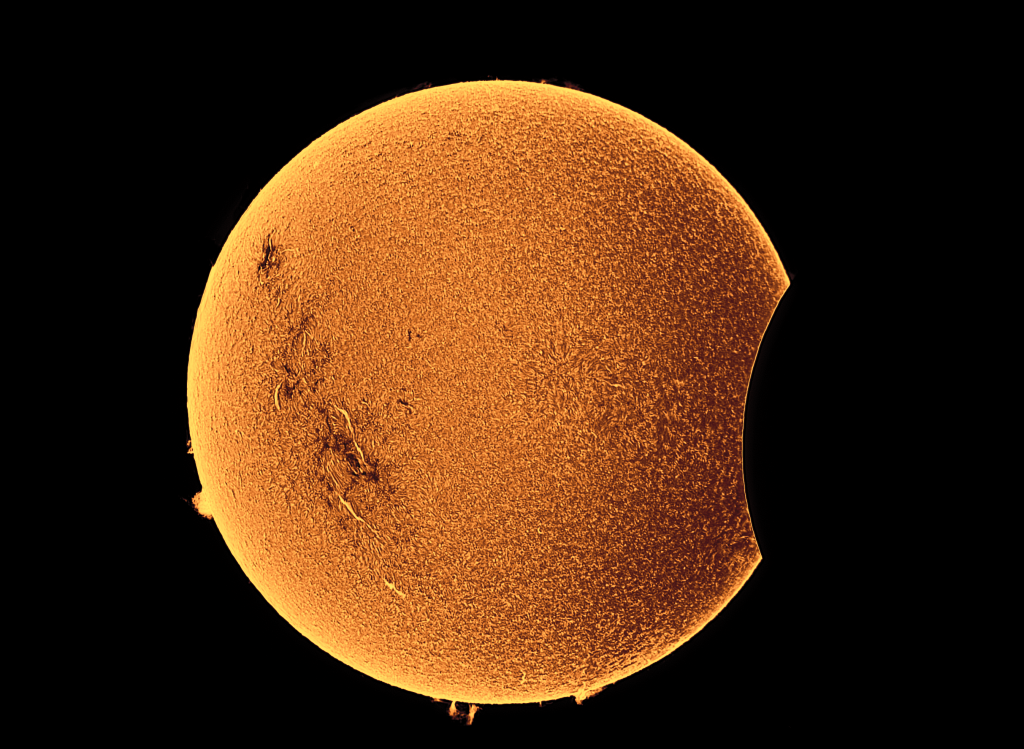

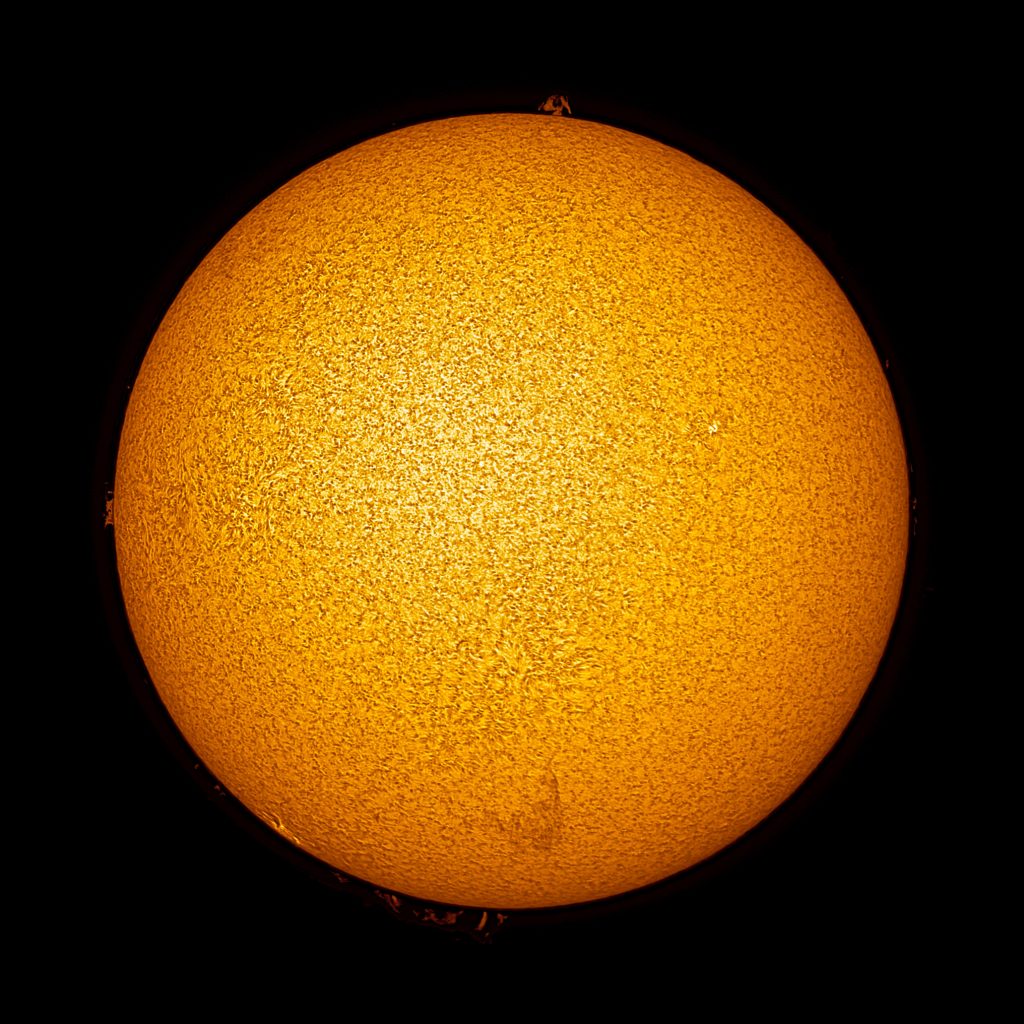

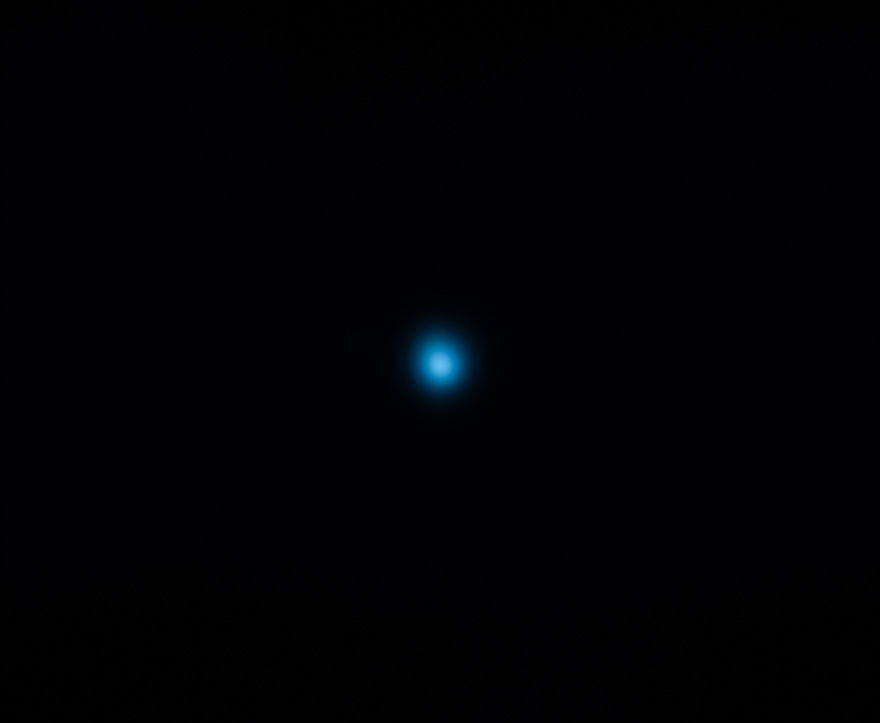

The sun is not shining on my terrace the whole winter. There is a small hill in the south direction, which blocks the sunshine. The situation gets better during the spring. The first rays show up in April when the sun gets higher in the sky. This weekend I managed to capture a few of them.

Quick description of the processing: Image acquisition in FireCapture. In total 4000 frames were recorded. Selection of 12% best pictures and stacking was done in AutoStalkert. The histogram of the picture was modified into an A-curve in ImPPG. The color was added in Pixinsight and the final adjustment in Adobe Lightroom.

| Telescope | Lunt 60mm |

| Aperture | 60 mm |

| Focal length | 420 mm |

| Mount | Rainbow Astro RST 135 |

| Camera | ZWO ASI 178MM |

| Filters | Double stack |

| Exposure | 4000x25ms, Gain 0, bin 1×1, 12% selected |

| Date | 2023-03-18 |