I have been searching for a wide lens for my recently astro-modified, second-hand Canon 6D. This means the lens should be suitable for a full-frame sensor 36 x 24 mm. The requirements on lenses are very tough for astrophotography because you photograph the stars – pinpoint sources of light. The design/manufacturing flaws of the lenses are revealed on every astrophoto and optical aberrations spoil the good shot. Astrophotography of the Milky Way needs a lot of effort. Specifically, you have to travel to reach the dark sky and if you do so, you want to make nice pictures. In my opinion, the lens is the most important piece of equipment for astrophotography, because nowadays you can buy second-hand Canon 6D, which is still very good and relatively inexpensive.

All the lenses are very sharp and aberration-free in the center of the picture, but the more you go off the axis, the aberrations start to pop up. There are many kinds of optical aberrations. A very nice article about the most common aberrations is on Lonely Speck.

Last year I purchased Samyang 14 mm f2.8, which is a great lens for the money, but the corners are not perfect and the stars are strongly deformed in every corner. I assumed that almost twice more expensive Samyang 24 mm f1.4 will perform much better and I also assumed that it’s easier to make a 24 mm lens compared to 14 mm. Moreover, f1.4 is a brilliant convincing argument. On the other hand, Samyang 24 mm doesn’t communicate with the camera, which means no EXIF of aperture and manual focus. This makes the lens a one-trick pony, suitable mainly for astrophotography and not that practical for regular photography.

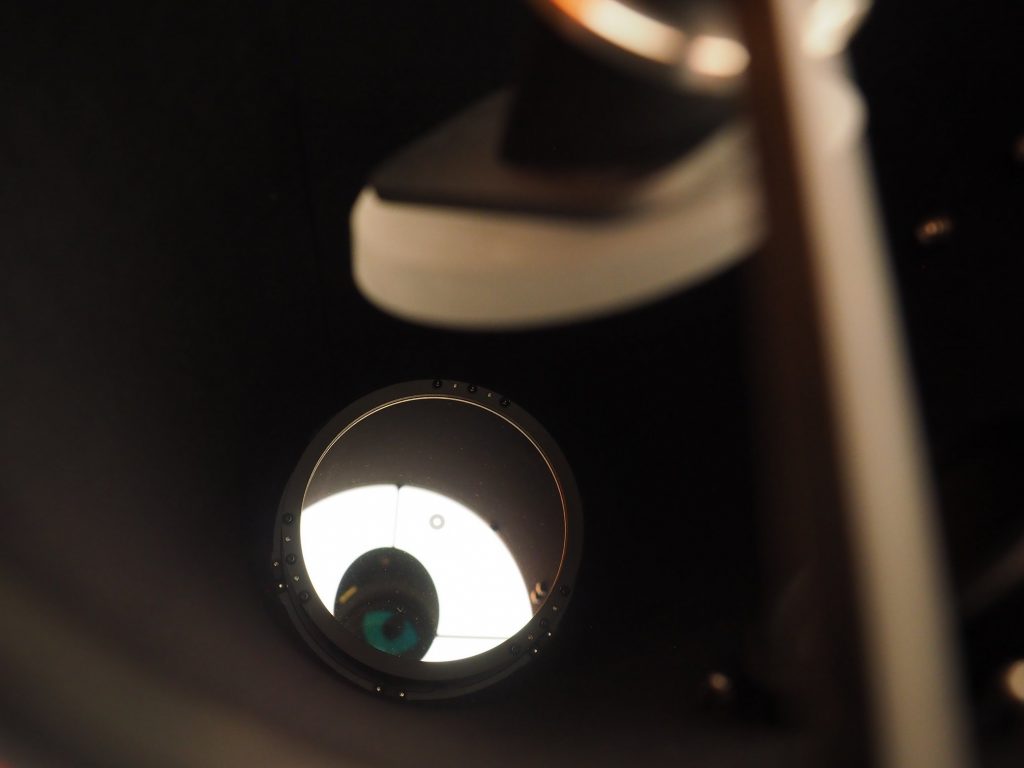

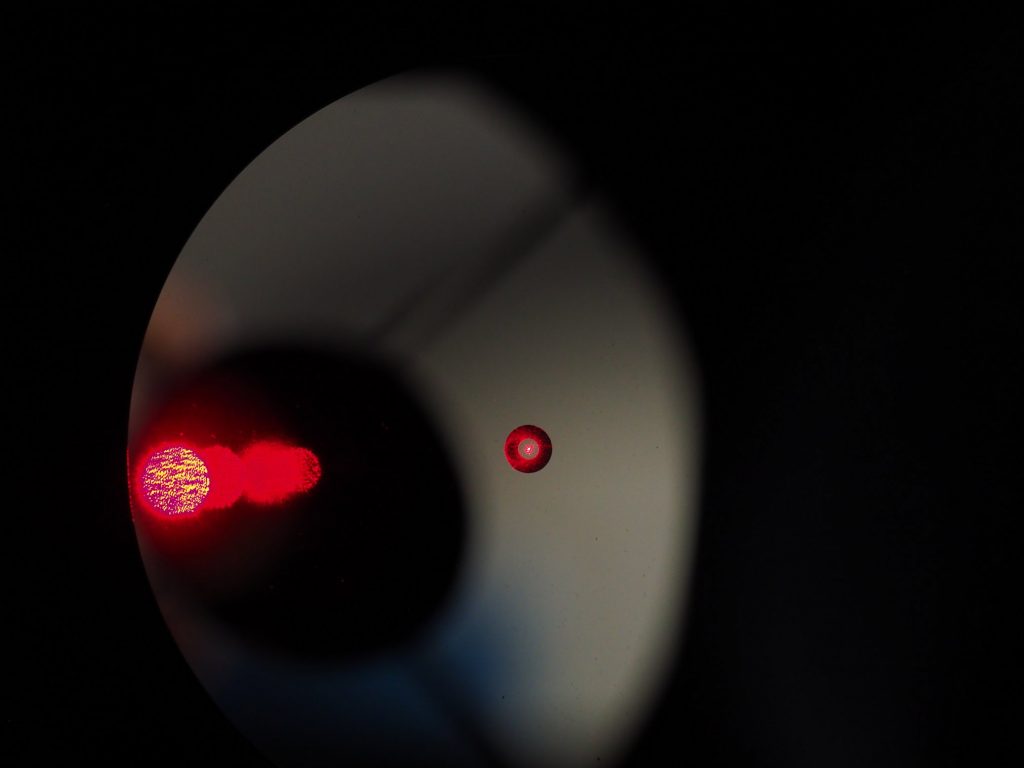

Before I take this lens to the dark site, I decided to test it from my light-polluted home. The equipment: Canon 6Da, Baader Nanotracker, and of course, Samyang 24 mm f1.4. The main aim was to find the best aperture/sharpness ratio. Most of the lenses get sharper if slowed down. So I kept the exposure time 20 s, ISO 800, and was systematically changing the aperture from 1.4 to 2.8.

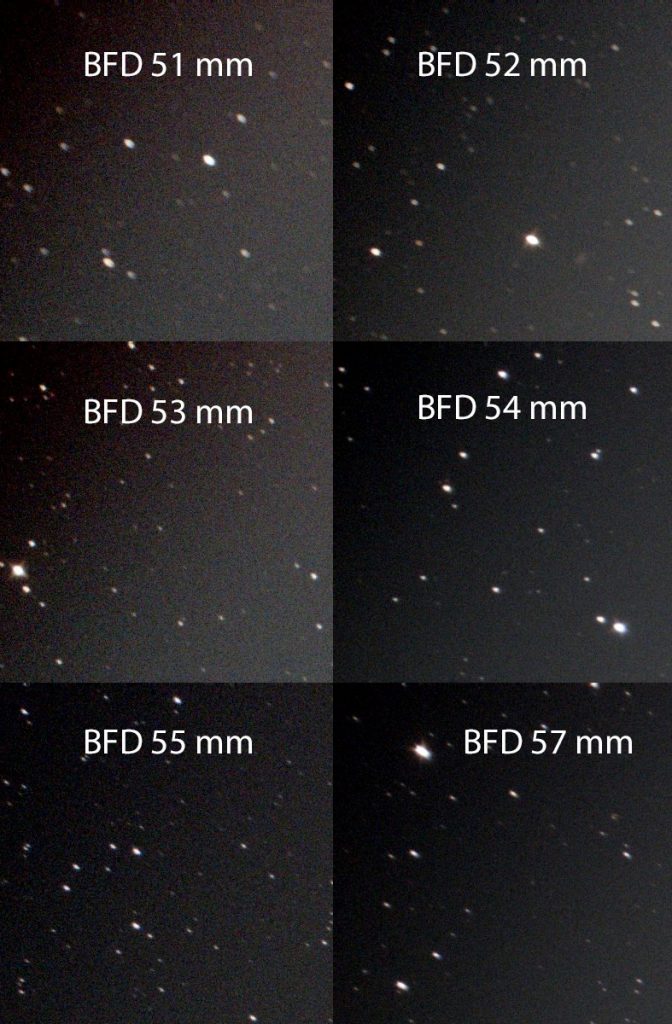

Here are the results of uncropped and uncorrected (no flats, no bias, no darks, and no noise reduction) pictures:

F1.4

F2.0

F2.4

F2.8

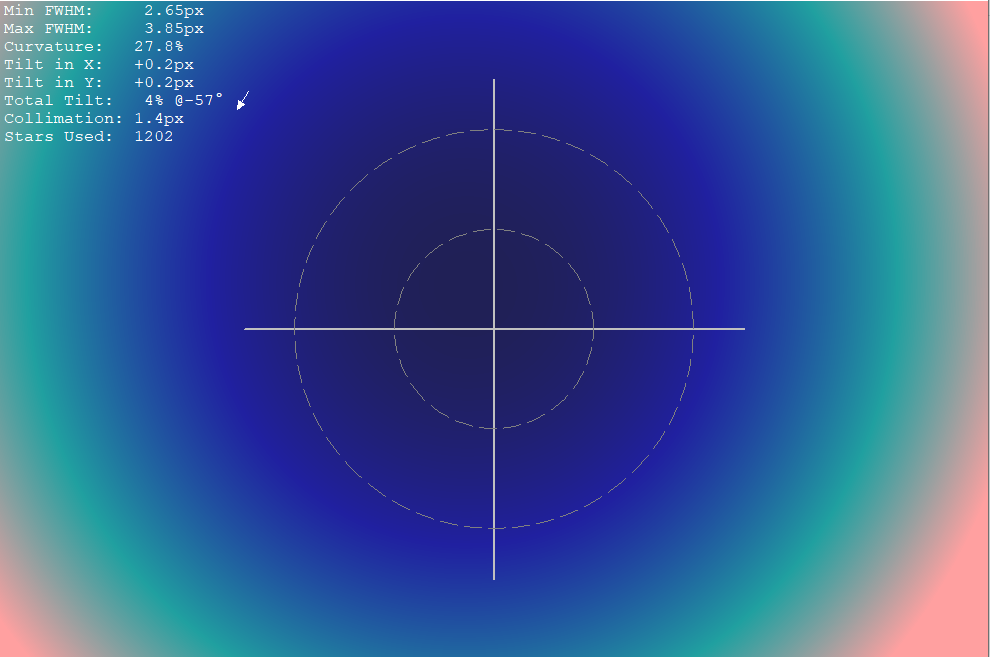

And the winner is…. obviously, the largest aperture (the smallest F number) collects the most of the light, but it vignettes strongly and honestly, the stars are ugly even in the center – this is totally unusable for serious astrophotography. The situation is not much improved by slowing the lens down to F2.0. At F2.4 the situation is significantly improved but at F2.8 the star roundness is acceptable almost everywhere, except the left corners.

Let’s have a look to the upper left corner – there the stars are the worst.

F1.4

F2.0

F2.4

F2.8

Conclusions

Samyang 24 mm F1.4 should be slowed down to at least to F2.4, to offer decent quality of the stars on a full-frame sensor. At F2.8 the quality is even slightly better, but at the top-left corners are the stars still elongated by astigmatic aberration. I expected better star quality, but in the end it’s not so dramatic, because the right side is not perfect, but acceptable. At least I know which side of the camera I should turn towards the ground if making a portrait picture of the Milky Way.